Humphrey de la Croix

Many Indos will find the movie ‘Buitenkampers’ a recognition of their history and even their entire existence during the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies and thereafter, late in coming and many see it as too little too late.

The Dutch history writers have always put the emphasis on the (Indo) Dutch who had been interned in the ‘Jap camps’. It is evident from the documentaries shown on television and in movie theaters, broadcasts on the radio and educational material. The majority of them were full blooded Dutch, although there was a substantial number of Indos who were also interned. The figure is around 20,000. The total amount of fair-skinned Dutch in the camps was 80,000.

Internment of all Indos took place outside of Java in the region under jurisdiction of the Japanese Navy. Indos who looked less Asian were interned on the island of Java where most of them lived. The Japanese used these standards rather randomly.

Of a total of 320,000 Europeans there were an estimated 220,000 who were not interned.

In fact, the history of the majority of the Europeans during the Japanese occupation has always been a non-issue. Actually there has been little or no attention paid to this data. What is the story here? I am trying to find a brief explanation.

The Japanese occupation: Indo-Europeans in limbo and outlawed.

Next to uncertainty about present and future humiliation, suffering, harassment and violence in various ways; war meant loss of freedom and for many poverty through loss of employment and other sources of income. Many Indonesians welcomed their Japanese fellow Asians. In the beginning they could not know that it was going to be worse than under the Dutch.

The humiliation of Europeans by an underrated Asian power stripped the Indo-European of their status at the top of the colonial social pyramid. Although they were aware of their indigenous roots, in daily life they were part of the European society in an Indonesian environment. After the fall of the Dutch East Indies it showed just how much they were alienated from their native roots. Indonesians felt freer and showed how they felt towards the Indos. The loyalty of the Indos towards The Netherlands and the Dutch people was seen as co-suppression of the Indonesians. The resentment surfaced and the Indos faced intimidation and aggression by the Indonesians who were supported by the occupiers. The Japanese did everything to eliminate the European element. Amicably at first, they approached the Indos in a friendly manner and endowed them with a so called role in the Greater East Asian Prosperity Sphere. When the response wasn’t forthcoming they tried to force the Indos to work in amongst other things, agricultural colonies. One effect was that there were Indos who were willing to work together with the Japanese. An example is Piet Hein van den Eeckhout who was charmed by the by the Asian kinship between the Indos, the Japanese and the Natives. Although the group was small, the cooperative Indos had key positions in these camps.

Another effect of the Japanese propaganda was the enticement of the native population against the Dutch and therefore also the Indos. They were seen as traitors to their Asian brothers. The Indos faced more and more provocation, intimidation and aggression. How bad it would turn out to be, would be evident in the period after August 17, 1945.

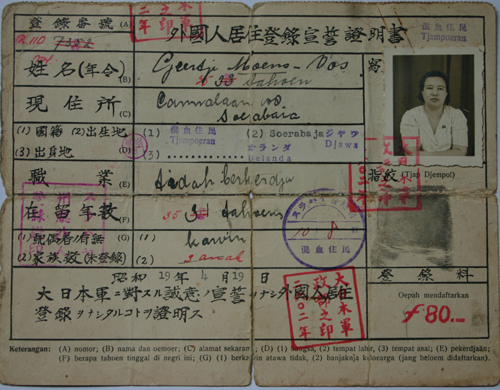

Pendaftaran (identity card) of Geertje Vos (mother of Ria Reijerse-Moens)

Scan: H. de la Croix

Ignored and Untold Stories: Causes and Explanations

‘Indo silence’: feelings of shame and humiliation are too painful.

Buitenkampers who did not want to accept the fact they were ignored, emphasize that they also are part of Dutch history, and make up an active minority within the Indo community. Most Indos who remained outside the camps have never en masse revealed what happened to them during the war and the Bersiap time. If they would tell about it, it was in the closed world of their own families and intimate circles.

That’s why I don’t know too much about the experiences of my own family (from my father’s side) during the war and the era 1945-1949. Not until later did I hear about the search for a successful refuge in the hilly regions of East Java. Many peers my age will recognize this and with regret now have to conclude that there are no or few members of the older generation left whom to ask questions.

In any case, silence of the ones involved is the reason a major source in documenting their history is missing. My generation and the next have become more and more dependent on indirect information sources as far as the people outside the camps are concerned.

The German concentration camps as the standard yardstick of victimization?

After Auschwitz the concentration camp became the unmistakable moral yardstick to test the evil and through it the endurance of victimization. Unfamiliarity in The Netherlands with the war in the Dutch East Indies is the basis of identification of said war for the Dutch people who had been in camps. From the stories of people out of the Dutch East Indies who reached their families in The Netherlands, the Japanese camp soon defined the picture of how bad it had been, particularly for the Totoks. After the war, such a picture has put a fixed image in the collective memory of the Dutch people. To this date this finding is confirmed by recent documentaries and publications. ‘Yes in the Dutch East Indies you also had concentration camps and for us (Totoks) the suffering was also great’.

This incomplete and partly inaccurate image (the Japanese camps were not concentration camps) was due to the fact of the heavy normative connotations and the inability to show any gradation and to supplement it with the story of the Buitenkampers who were also victims. In attempts to draw attention to them a lot of Indos (but also Totoks) use the term ‘concentration camp’ although historically inaccurate, from a human standpoint it is understandable.

Extroverted Totoks versus Introverted Indos?

A question could also be why the experiences of former internees of the Japanese camps have become so much better known and now regularly appear in publications? Does this point to a difference in behavior between the mostly Totok internees and the Indo-Europeans who stayed outside the camps? With the exception of those who have fought for attention in recent decades this indeed seems to be the case.

The feelings of pain and humiliation and the disregard inflicted by Dutch politics and Dutch society after repatriation can never be undone. Indos have signed up in large numbers for Indo-European academic seminars since 1989 and the 1989 showing of the documentary ‘No ordinary Indo girl’ by Marion Bloem and most recently the film’Buitenkampers. Boekan Main- Boekan Main.’

However, to explain the cause of disregard of the Buitenkampers’ history from arbitrary and tainted behavioral characteristics has no basis in objectifiable facts. So as an historical explanation this is unusable. Perhaps the greater focus of the Totoks on reading and writing versus the Indo tradition of verbally conveying a story in a way would explain why the Totoks by putting down their experiences in writing simply could attract faster and broader attention.

It is encouraging that for some time now the Indos slowly but surely are catching up somewhat.

The ’hierarchy’ of endured suffering and traumatization.

When Het Gebaar was made public in the years 2002-2003 the discussions about discrimination in treatment and financial compensation were getting somewhat smelly. What I mean by this is that from the Dutch-Indonesian perspective the impression was given and suggestions were heard that the government assigned greater suffering to the Jewish victims of war and the Gypsies than those who suffered in the Dutch East Indies. The discrimination would manifest itself in lower payments to the Indo victims. This suggestion was understandable as an emotional expression but of course difficult to substantiate with evidence. This would have been reflected in the legislative history of Het Gebaar. There is no evidence that the government has made considerations pointing in the direction of unequal treatment, but one effect was the feeling that the Buitenkampers still did not matter a whole lot any more. Even after all these years and after so much new historical information, experiences and political actions by the Dutch/Indonesian community.

Dutch postcolonial trauma: forgotten and the return to the order of the day.

After the Japanese surrender, the motherland did not really want to accept the loss of the Dutch East Indies. Only after almost 5 years of ‘police actions’ between 1945 and 1950 and despite the negative world opinion (changing times: colonialism and enslavement of peoples is wrong), The Netherlands had no choice but to acknowledge the Republic of Indonesia and give sovereignty to the country. A United Kingdom as a kind of Dutch Commonwealth, the United States of Indonesia and the refusal to surrender New Guinea was a last-ditch unrealistic effort to remain in the archipelago. When all of this definitely became unglued in 1962, for years The Netherlands did not want to look back at what had happened.

From a standpoint of a postcolonial power important questions should have been raised:

- Where do we stand as a former colonial power?

- What does the loss of the Dutch East Indies mean for both the Totoks and the Indos?

- How should the military and the veterans look back at their stake in those days?

- What image of their country should the Dutch have now that it is no longer a vast empire?

- Was assimilation the only way to integrate the Dutch/ Indonesian repatriates?

- What about the outstanding items like the arrears of salary payments and restitution in connection with damages and loss of property?

- The cold reception of the repatriates and why many have migrated to better regions?

- What about the excessive use of force committed by the Dutch military?

- And of course: what about the Europeans who stayed outside the Japanese internment camps?

Postcolonial assimilation: still no catch-up day 1990 to the present?

For a long time the Dutch governments did not even asked themselves these essential questions. But in due time the authorities were forced to examine these questions one by one. The number of contemporaries dwindled down from natural causes and therefore in time the emotional charge to ask these questions lessened and new generations of historians, lawyers, different researchers and journalists asked these old questions in an uninhibited way.

During the nineties of the last century Prime Minister Ruud Lubbers re-opened the ‘Dossier’. The Broad historical research was followed by actions such as research into the back pay of outstanding salaries and pension payments, the restitution of damage, not to mention Het Gebaar and the creation of a Dutch/Indonesian memorial center about the war and the bersiap time

These gestures by the government were deemed insufficient by the Indo community. Assistant-Secretary Marlies Veldhuijzen-van Zanten’s position in 2011 was clear. No new debate about rehabilitation and back pay of outstanding salary and compensation for officials and KNIL soldiers who were in Japanese prison camps during World War II.

Because of this abrupt disposition she was reined in by the Standing Parliamentary Health Committee the VWS department (Public Health and Sports). The Rutte II Cabinet has now opened the door for a re-opened discussion. What is likely to be achieved is not clear. And in the mean time the private initiatives that fit into the post-colonial historical context continue. Lawyer Liesbeth Zegveld achieves success on behalf of Indonesian widows in the liability of the State for the death of Indonesians as a result of excessive use of force during the time period 1945-1949. This concerns the events in the West Javanese region of Rawagedeh and in South-Sulawesi that have to do with the actions of special forces’ Captain Westerling at the time. The government is obviously scared to death of many more claims and not in the least of those coming from the Dutch/Indonesian corner.

The movie: ‘Buitenkampers. Boekan main-Boekan main’ by Hetty Naaijkens-Retel Helmrich now also fits in the process of the postcolonial Dutch-Indonesian trauma; a long-anticipated attention for the neglected and almost unknown group of fellow citizens. Unfortunately, up until now, despite the reopening of Dutch/Indonesian records over the past twenty years, it is ascertained that the ‘forgetting’ of the Buitenkampers remains a constant. We should not forget that the movie ‘The year 2602. Childrens’ stories from the Japanese camps 1942-1946’ was preceded by ‘Buitenkampers.’

A hefty dose of criticism came from the Dutch-Indonesian community about the high percentage of ‘white’ in this 2009 movie. The agonizing point was that the movie did not show the considerable percentage of Indos who were also in those camps. Soon a plan originated to eradicate this inaccurate image. The outcome is not a documentary about the Indos inside but outside the camps. The question is whether the first critical point can still be accommodated.

All in all it can be said that the lack of a postcolonial debate after the loss of the Dutch East Indies/Indonesia the Dutch state will continue to be ‘haunted’ from within the Indo corner. The next generation has received the unpaid bills as a Dutch/Indonesian cultural heritage and will continue on this path.

In the mean time we as a historical website carry a full time responsibility towards the Dutch/Indonesian community to find out and record the life stories of the Buitenkampers. Maybe a modest contribution in scope, but we are fortunately not the only ones doing it.

Histories of Buitenkampers on the website: IndischHistorisch.nl

What exactly is the subject to be studied? The starting-point of this website is the history of the Indo/Dutch in general. From a historical-scientific perspective Buitenkampers is a neglected subject. The fact that such a substantial group in a heavily studied period never made it into the agenda is not only remarkable and amazing. Even painful for all those Indo/Dutch who still simply made up an integral part of Dutch history.

Therefore this is more than enough reason to highlight this overdue history more intensely. There were obviously already some writings about individual life stories in particular those that were released in the past 15 years. Also because of the realization that time is of the essence because the group from that time period itself is disappearing.

A comprehensive piece of work about the group the Buitenkampers still doesn’t exist by far. First of all, sources of information have to be collected. In particular: information from oral history, self directed documents like notes, diary entries, drawings, archives if any (Japanese and Dutch) and movies, photographs and audio material. Finding and recording of individual life histories will now be a high priority given the time that has been lost. The Indisch-Historisch.nl website will be alert in this respect.

Publications about the Buitenkampers on: Indisch-Historisch.nl (in dutch)

Ria Reijerse-Moens: ‘Kind buiten het kamp in Surabaya’

‘Repatriëren als verstkeling. Deel 7: Edward Jacobs (1) ‘Tijd in Indonesië tot 1950’

‘Dampit en andere Malangse herinneringen van Martin Berghuis.’

Information on the Internet (dutch websites)

www.buitenkampkinderen.nl

www.buitenkampers.nl

www.indieinoorlog.nl

www.idischekamparchieven.nl

Literature

Tjaal Aeckerlin and Rick Schoonenberg. ‘De jaren van asal oesoel’. Dutch/Indonesians during the Japanese period. Amsterdam 2006.

Beatrijs van Agt, Florine Koning, Esther Tak, Esther Wils ‘Het verborgen verhaal’. Dutch/Indonesians during the war 1942-1949. The Hague (No date).

Lizzy van Leeuwen ‘Ons Indisch Erfgoed’. Sixty years of struggle about culture and identity. Amsterdam 2008.

Ilonka de Ridder (composer and editor). ‘Eindelijk erkenning’? Het Gebaar:

(The contribution to the Dutch/Indonesian community). The Hague/ ‘sHertogenbosch 2007.

Rita Young and Zwaan de Vries ‘ War and survival outside the Japanese camps:’three generations tell their stories. Nijmegen 2008.

Media

Buitenkampers, Boekan Main, Boekan Main! from hollandharbour on Vimeo.

Trailer documentary ‘Buitenkampers. Boekan main! Boekan main’. Directed by Hetty Naaijkens – Retel Helmrich

Rita Young tells her story about life outside the Japanese internment camps in former Netherlands Indies

Pingback: Second World War and Bersiap Period(1945-1949): Buitenkampers Neglected and Untold Stories |

Pingback: Landscape of the Soul – Indonesia’s Forgotten History – Our Indonesia Today