Humphrey de la Croix

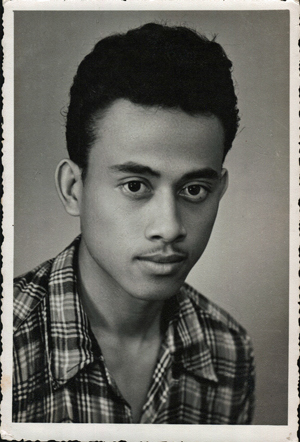

Harley Driessen is born January 21st, 1935 in Semarang, Central Java in the former Netherlands Indies (Indonesia). Seventy years later he easily evokes the memories of his childhood during the Japanese occupation period and the perilous years of Indonesian war of independence against the Dutch from 1945 till 1950 . Like so many other Indos Harley Driessen repatriated to the Netherlands. His country of birth no longer guaranteed him the perspectives of job and his personal security. In 1956 he arrived in his fatherland that he only knew from his school lessons. But there too he noticed how difficult it was to find a job. Like so many other Dutch and Indos the young migrant decided to move to the United States, the promised land of the unlimited opportunities. In 1960 Harley Driessen disembarked in Hoboken, New York. A new life had started.

Harley Driessen is born January 21st, 1935 in Semarang, Central Java in the former Netherlands Indies (Indonesia). Seventy years later he easily evokes the memories of his childhood during the Japanese occupation period and the perilous years of Indonesian war of independence against the Dutch from 1945 till 1950 . Like so many other Indos Harley Driessen repatriated to the Netherlands. His country of birth no longer guaranteed him the perspectives of job and his personal security. In 1956 he arrived in his fatherland that he only knew from his school lessons. But there too he noticed how difficult it was to find a job. Like so many other Dutch and Indos the young migrant decided to move to the United States, the promised land of the unlimited opportunities. In 1960 Harley Driessen disembarked in Hoboken, New York. A new life had started.

Arriving in the Netherlands

After approximately 28 days Harley Driessen arrived around August 1956 in Rotterdam, the second biggest city of the Netherlands. He went almost immediately to Den Haag in a boarding-house (pension) called ‘De Rijk’. Several other boys and girls of different ages were sent to that place. The pension was located in the 125 Nieuwe Parklaan in Scheveningen, the neighbourhood of Den Haag at the North Sea. The boarding-house was meant to be a temporary shelter. In the meantime the Dutch governement was trying to find a more permanent housing, or better: a real home.

After approximately 28 days Harley Driessen arrived around August 1956 in Rotterdam, the second biggest city of the Netherlands. He went almost immediately to Den Haag in a boarding-house (pension) called ‘De Rijk’. Several other boys and girls of different ages were sent to that place. The pension was located in the 125 Nieuwe Parklaan in Scheveningen, the neighbourhood of Den Haag at the North Sea. The boarding-house was meant to be a temporary shelter. In the meantime the Dutch governement was trying to find a more permanent housing, or better: a real home.

For the time being Harley had to share his ‘home’ with some 25 or more others.

The first part of Harley Driessen’s story ended with his departure from Indonesia. In this second article we will understand why he left the Netherlands.

No Income: Dutch Government paid advances

As long as Harley did not have a job the Dutch government paid an advance of 3 guilders a week (at that time less than 1 dollar) for small personal expenses like soap, tooth paste, candy, a ticket for the movie, ice cream and stuff like that. The clothes, fit for the West-European climate, had been distributed during the voyage from Indonesia to the Netherlands. In Port Said in Egypt the Dutch government had furnished a set of clothes. These also meant as a payment in advance. The basic set consisted of a pair of pants for daily use, a shawl, a beret and a pair of woolen gloves. Later, in the Netherlands under guidance of a supervisor (a social worker or other civil servant) Harley shopped for a costume and a winter coat. The supervisor made sure not to overspend the allocated money. The costume was meant to wear only on Sundays and at official occasions. All the tropical clothes brought from Indonesia were not fit for use in the Dutch winters.

As the paying back of the loan should start after 5 years the government had forgiven Harley Driessen’s loan. He emigrated to the United States two and a half years after his arrival in the Netherlands.

From The Hague to Rotterdam

After two weeks in pension-De Rijk, Harley Driessen moved to Rotterdam. The boarding house was located in the Hooglandstraat, in the northern part of the city. He felt disappointed because he had to share the place with five the other boys. It made him feel being back in the orphanage. He dared not to complain as everything was given to him and with all the best intentions, even he had to pay it all back later.

Daily life in the pension (boarding-house)

This specific aspect of the Indos’ initial life after setting in the Netherlands is an often told story and has become a lasting item in the collective memory of the Indo repatriates. The ‘contractpension’ is the symbol of a cold (not warm-hearted) treat and displacement. The tropical warmth, the life outside the houses and the formidable food supply were further away than ever.

Harley Driessen describes the daily routines of the pension:

“At breakfast we ate bread, strawberry jam, cheese and milk. At lunchtime we ate bread with some slices of meat and milk. Dinner consisted of boiled potatoes and a small piece of karbonade (pork chop). Twice a week we had the opportunity to eat a dish of the Indonesian cuisine. We enjoyed the luck of having a Dutch-Indonesian (Indo) woman cooking and she was a very good cooke. I was Always looking forward to those two days.

When dinner was finished we had our leisure time and we could do anything we wanted to do. Most of the time I stayed at ‘home’ in order to prevent myself to waist money. I did not like the feeling not having money in case I would needed it urgently.

In the pension we were subjected to a curfew. We had to be back at a certain time (I don’t remember at what time exactly). Although already 22 years old I then had no other choice than go to sleep.”

Daily Food: the Dutch Style or ‘Customization’ of the Portions

Coming from the Indonesian tropical circumstances with their abundant supply of dishes, snacks and fruit, Harley Driessen had to cope with the ‘calvinist’ interpretation of life. The Dutch idea of ‘food is just to keep yourself alive and not for joy’, was directly visible in the daily food supply in the pensions. In addition the years of reconstruction and scarcity after the Second World War had strengthened the calvinist idea of sobriety and the ethic of hard working.

Harley Driessen:

“The night before you went to work the landlady sked you how many slices of bread you wanted to take to work. She then prepared your lunch package. When you came home form work she asked you how many potatoes you wanted. We all ate together at the same time. When dinner was ready she called all of us to come down to eat. The typical Dutch dinner was very simply composed and consisted of boiled potatoes, vegetables and a small piece of cooked meat. At that time I still was not used to the Dutch ‘cuisine and I never ate much. Fortunately one of the boarding boys was able to prepare (only one type) an Indonesian dich. On Saturdays after working time (half of the day) he made us a lunch. He cooked some rice and a kind of soup ith fish… It was not that good but it tasted better than potatoes.”

The Repeatedly Told Bathing Experience in the Netherlands of the Fifties and Sixties

Ask Indo repatriates about the bathing habits in the Netherlands, they all will tell the same stories. First there was the frequence of showering or taking a bath only once a week. If the house did not even have a bathroom you had to go outdoors to a public ath house. So did Harley Driessen:

“The house had no shower room. In summer as well in winter once a week we walked down the street to go to the publiek badhuis (bath house) which fortunately was not too far away. In tropics we were used to take a bath every day and several times. In the Netherlands they advised you not to take a bath every days as you would risk to scrub all the protecting skin grease from your body. That protecting layer was a necessary element against the cold winter period. Plus it was too expensive to take a bath every day.”

Harley resumes:

“You walk to the bath house with your towel, soap etcetera and wait for your turn.

There were a lot of people. There were a lot of shower cubicles. When it was your turn a woman assigned you to one of the cubicles that became available. She set the allowed minutes on the clock that was fixed on the cell door. Then you had to undress quickly as you could and take the shower. When your time was up the water supply shut off automatically. You had to make sure to be ready then and not still being covered by soap or with shampoo in your hair. I don’t remember how I was dressed but I won’t forget it was very cold outside.

Funny, after you took a shower you smell like roses and so did the whole bathhouse with all the people in it.”

Harley Driessen and his wife Maudy Pereira having a ride on a ‘bromfiets’, a light motorcycle popular in the fifties and sixties as an affordable means of transportation.

Finding a Job

In Rotterdam Harley Driessen also found a job with help from his landlord. Shipyard Wilton-Fijenoord in Schiedam offered him a training first in order to employ him as a boilermaker. It was a very tough fysical job 48 hours a week from Monday till Saturday.

Personally Harley prefered to work as a draftsman in an office but his diplomas from Indonesia were not valid in the Netherlands. Later, when he left the shipyard his manager told him his job actualy was meant for fysically stronger and bigger men. It was a good decision to stop as continuing could cause an burnout. Harley Driessen then realized becoming a draftsman in the Netherlands was not achievable. For the first time the idea of more and better opportunities in the United States came up and would result in emigration to that land of “unlimited opportunities”.

Moving Again: More Privacy and Freedom

The reason Harley Driessen asked his social worker to find him a new home, was the lack of privacy and the feeling of being back in the orphanage with it’s strict rules and overall control, where he had spent over 13 years. Being a young man now in his early twenties he needed an appropriate housing and to feel free. Harley Driessen now moved to an appartment in the Tapuitstraat in the neighbourhood Charlois, in the southern part of Rotterdam. His new landlord and landlady were the Bioch family. The landlady’s mother was an Indo woman who cooked the Indisch food for the family and the new tenant Harley. This was substantial step forward compared to the food situation in the boarding house. And more important: he had more privacy.

Reunion with his Brother Robert

In 1958 Harley Driessen could welcome his brother Robert and sister-in-law. Although newly arrived they did not have wait a long time before getting a house. Finally Harley had found a real home. The appartment was in another part of Rotterdam, in the Geertruidenbergstraat situated in Pendrecht neighbourhood. Harley would stay there until he left for the United States. His brother’s first child, a boy, was born in that house and six month before his departure to the States.

Harley Driessen: “I was very happy to live with my brother because now I was with family and I ate Indonesian food every day. My brother is a good cooke”.

Harley Driessen and Maudy Pereira in their twenties and just married

Maudy Pereira, Harley’s wife, with her own bromfiets, a lighter model fit for women

Preparing the departure

Harley Driessen was one of the many Indos tooking advantage of the Pastore Walter Act. He had to submit a screening process that was a whole day affair and was done in Rotterdam only. Elements of the screening were a health check and was one able to have a valid passport.

The American consulate’s main questions were:

1. Which state do you prefer to go?

2. Do you have already have a co-sponsor?

Like most Indos I prefered to emigrate to the ‘sunshine’ state California. Finding a sponsor was not a problem as Harley Driessen with the status of bachelor had a so-called ‘open placement’. The US officials selected a sponsor but they could place you anywhere in the USA. The sponser selection was based on your religious denomination. Therefore Harley Driessen’s sponsor was the National Catholic Welfare Conference (NCWC). Actually the officials advised him to opt the Church World Service (CWS) as this sponsor would give a better deal. After passing the screening test it was just a matter of waiting for the first available passage to the United States.

Emigration to the United States: Some Notions about the US immigration policy

Some background information could be useful to understand Indos initial problems to migrate to the United States in the fifties of last century (HdlC).

Migration to the United States occurred under legislative refugee measures, these immigrants were sponsored by Christian organizations such as the Church World Service and the Catholic Relief Services. An accurate count of Indo immigrants is not available, as the U.S. Census classified people according to their self-determined ethnic affiliation. The Indos may have been included in overlapping categories of “country of origin”, “other Asians,” “total foreign”, “mixed parentage”, “total foreign-born” and “foreign mother tongue”. However the Indos that settled via the legislative refugee measures number at least 25,000 people.

The original post-war refugee legislation of 1948, already adhering to a strict ‘affidavit of support’ policy, was still maintaining a colour bar making it difficult for Indos to emigrate to the USA. By 1951 American consulates in the Netherlands registered 33,500 requests and had waiting times of 3 to 5 years. Also the Walter-McCarren Act of 1953 adhered to the traditional American policy of keeping down immigrants from Asia. The yearly quota for Indonesia was limited to a 100 visas, even though Dutch foreign affairs attempted to profile Indos as refugees from the alleged pro-communist Sukarno administration.

The 1953 flood disaster in the Netherlands resulted in the Refugee Relief Act including a slot for 15,000 ethnic Dutch that had at least 50% European blood (one year later loosened to Dutch citizens with at least 2 Dutch grandparents) and an immaculate legal and political track record. In 1954 only 187 visas were actually granted. Partly influenced by the anti-western rhetoric and policies of the Sukarno administration the anti-communist representative Francis E. Walter pleaded for a second term of the Refugee Relief Act in 1957 and an additional slot of 15,000 visas in 1958.

In 1958 the Pastore-Walter Act (Act for the relief of certain distressed alliens) was passed allowing for a one off acceptance of 10,000 Dutchmen from Indonesia (excluding the regular annual quota of 3,136 visas). It was hoped however that only 10% of these Dutch refugees would in fact be racially mixed Indos and the American embassy in The Hague was frustrated with the fact that Canada, where they were more strict in their ethnic profiling, was getting the full blooded Dutch and the USA was getting Dutch “all rather heavily dark”. Still in 1960 senators Pastore and Walter managed to get a second 2-year term for their act which was used by a great number of Indo ‘Spijtoptanten‘ (people who regretted having op for Indonesian nationality).

Be continued