Humphrey de la Croix

Harley Driessen is born January 21, 1935 in Semarang, Central Java in the former Netherlands Indies (Indonesia). Seventy years later he easily revokes the memories of his childhood during the Japanese occupation period and the perilous years of Indonesian war of independence against the Dutch from 1945 till 1950 . Like so many other Indos Harley Driessen repatriated to the Netherlands. His country of birth no longer gueranteed him the perspectives of job and security. In 1956 he arrived in his unknown fatherland. But there too he noticed how difficult it was to find a job. Like so many other Dutch and Indos the young migrant decided to move to the United States, the country of the unlimited opportunities. In 1960 Harley Driessen disembarked in Hoboken, New York. A new life was waiting in front of him.

Harley Driessen is born January 21, 1935 in Semarang, Central Java in the former Netherlands Indies (Indonesia). Seventy years later he easily revokes the memories of his childhood during the Japanese occupation period and the perilous years of Indonesian war of independence against the Dutch from 1945 till 1950 . Like so many other Indos Harley Driessen repatriated to the Netherlands. His country of birth no longer gueranteed him the perspectives of job and security. In 1956 he arrived in his unknown fatherland. But there too he noticed how difficult it was to find a job. Like so many other Dutch and Indos the young migrant decided to move to the United States, the country of the unlimited opportunities. In 1960 Harley Driessen disembarked in Hoboken, New York. A new life was waiting in front of him.

World War II Through the Eyes of a Child

As a young orphan without family he had to spend his life in several institutions and each of them belonging to specific Roman Catholic monastic order. 1) In Harley’s case:

a. Kindergarten, Institute for small children. The Institute is located in Salatiga. a town 25 km south of Semarang.

b. First grade in the Institute for girls. The Institute is located in in Gedangan Street(now: Jalan Ronggowarsito), Semarang. The institute belonged to the Congregation of Sisters of Saint Francis (Zusters Franciscanessen).

c. Second Grade and up, in the Institute for boys. The Institute is located in Karangpanas, Semarang.

“For safety reasons, the first graders, including me, were sent back to Salatiga. But now, instead of the ‘juffrouws’ (female teachers [HdlC]), a few uns came with us. We were too young to comprehend what was going on. What we did not know was that WW-II broke out.”

“Nearby our place the Dutch cavalry was stationed. I remembered the soldiers wearing nice Australian hats. One side was folded up. The horses were large and beautiful. The soldiers were also wearing sabres.”

The Salatiga institution was a kindergarten for boys and girls. The institution was also administered and owned by the Zusters Franciscanessen. It was located in a former convent in the Langensoeko quarter not far from the Julianalaan (Juliana walk), now the Jalan Kantor Pos, Post office street.

When the Japanese occupied the Netherlands Indies after the Dutch capitulation March 9, 1942 Harley went back to his town of birth, but now had to move into the Rooms-Katholieke Weeshuis Tjandi (Roman Catholic Orphanage). This orphanage belonged to the fraternal order of Saint Aloysius of Oudenbosch (a Dutch order) and it was located in the Oud-Tjandi (Old Tjandi) neighbourhood of Semarang, more precisely in Karangpanas Street.

Semarang: Rooms-Katholiek Weeshuis Tjandi(right) (Roman Catholic Orphanage Tjandi).

Left: Roman Catholic Church Karangpanas

Foto: http://julieallebewijzen.blogspot.nl/2013/09/heilige-antonius-beste-vrind-maak-dat.html

Young Harley noticed the world around him was changing:

“Then one day, all sudden the Dutch army disappeared. Instead, we saw these people, smaller in size, with slanted eyes, and wearing different uniforms. It turned out they were the ennemy. The Japanese invaded the Netherlands Indies. The nuns told us not to talk to them. They were afraid we may upset the Japanese soldiers.”

The Japanese occupation had an immediate impact on daily life:

“All Dutch education had to stop. Alle family pictures of the Dutch queen, including calendars with the royal familiy on it, had to be burned. We were not allowed to speak Dutch openly.”

Harley remembers one day the Dutch priest, Pastoor Winkel, came to say goodbye to them:

“He was fully dressed in the Dutch army uniform. I believed that later on he became a POW. After the war he came back and continued what he was doing before the war started,namely looking for the Dutch-Indonesian children (Indos) and put them into the Roman Catholic Orphanage [in order to] give them a better education and last but not least converting people to the Roman Catholic faith.”

Daily Life in the Orphanage

Although the orphanage actually was not a camp of refugees, the Japanese ordered that we had to share our facility with the people from of the Institution for girls (Gedangan) and the people (they are families!) of the Institution of the Protestant Faith. The reason was that the Japanese wanted to occupy their buildings.

Harley Driessen tells about the daily routines:

“A brother woke us up, we got dressed and attended the mass. Then we had breakfast and played in the inner playground. After a while we had ‘soos time’.”

“During this time we had to be quiet. We have to read a book or do something else. The main thing we were not allowed to talk to each other.

“I was happy because finally I was able to see two of my brothers. The oldest one was in active duty in the navy. I heard later he was interned in Japan. I was separated from my two brothers because they were in another section. I did not see them all the time. The older boys and the younger ones were not allowed to communicate with each other.”

Internment of the orphanage’s friars

Soon Japanese rule over the Indies affected daily life in the orphanage. All the friars (they were not priests but clergymen and the boys called them ‘brothers’) were herded together and the Japanese soldiers took them away. They only left two friars behind. One of German descent and the other an Indo, whom the Japanese considered as an Asian. Both men were already aged persons and had to take care of the boys. The same happened in the Gedangan institute for girls . The Dutch nuns were interned and replaced by Indonesian sisters. But the Japanese also took over the entire building of the institute and the girls had to move into the boys orphanage. They could use the empty sections of the interned friars. Now three different groups were housed in the building: the boys, the girls and the evacuees.

Harley Driessen:

“…eventually we had to move out. The Japanese wanted to convert our building into a camp for interned Dutch people and also as a residence for themselves. Under the covert part of the inner playground the carpenters were busy convrting our covered playground into one large sleeping arrangement made of wood. They built a wooden frame with legs entirely covering the playground. On top they put wooden planks where the interned people would sleep side by side.

By then all people of the three groups were moved to other locations. In our case we went to the Sint Jozefschool in ”

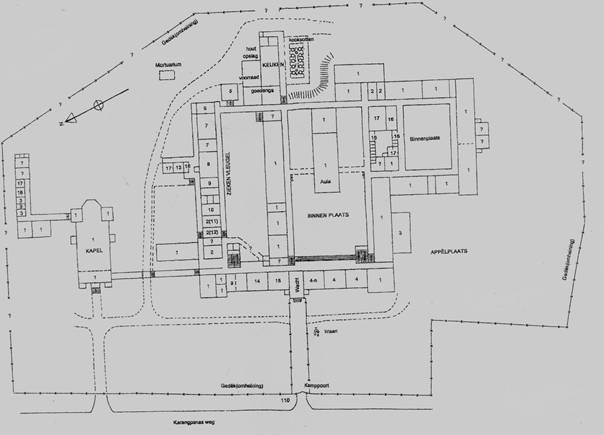

Map of Karangpanas internment camp for women and children. Before the complex was the Roman Catholic Orphanage for Boys (RK Jongensweeshuis).

Source: http://www.japanseburgerkampen.nl/KarangpanasE.htm

Sint Jozefschool in Semarang Bangkong

This stay would last until the end of the war. The two persons in charge were friar Petrus, an Indo man not interned age about 75 or more. The other man was Karel Bauwer a layman who after the war had been consecrated as a friar.

The total group counted 70 boys, maybe more. Every day they had several task to execute:

“Three older boys were assigned to do the cooking. Each one will cook for a week at a time. Every day they have to cook three meals and chop the firewood. I did not remember where tey got the firewood from. There was no gas for cooking. Cleaning the pots and pans was assigned to one of my brothers. There was no hot water, so they have to boil their water themselves. A number of the older boys, I believe ten, have to do the laundry. This was done by hand and the sun did the drying.”

Gardening

Beside the chors in the school building Harley and the other boys had to convert the yard, which was a field, into a vegetable garden in order to be selfsufficient. The older boys had to do the tougher work taht requiered the use of pacols (Indonesian hoes).

“…the boys from 14 to 16 years old had to make row and rows of beddings. After the bedding was ready we kids had to break the soil, pull out all the grass and weed. We had to do this under the burning tropical sun from breakfast time till noon. We have to do this every day of the week except Sundays. Of course kids rather play than work. Sometimes we slowed down. When the supervisor saw this he would sneak behind us and threw a piece of clay on our backs. He did not say anything but we got the message and started working again. When the beddings were ready we planted vegetables like spinach, mungo beans, peanuts and other bean varieties. Where the dug-out shelters were located we planted cassave. You can eat almost everything what the cassave root produces. All you have to do is putting a piece of cassave into the soil in the right way. It is said that putting upside down the root you will be poisoned!” 2)

The Spinning Wheel

One day the boys were assigned to produce yarn. In order to realize this goal the Japanese supplied a spinning wheel and hemp, the basic material to make the fabric.

“From that day on, till the day we moved out of Sint Jozef School, we had to produce yarn in lieu of working in the yard.”

“The spinning wheel was operated by one person, sitting on a bench. Once a week a Japanese person collected the spools of yarn. Each kid had to produce 100 grams of yarn every day. That was a lot of work but we had to follow the orders otherwise supervisor Karel Bauwer (Bauer?) would be in trouble. 3) If everything went smoothly we had a better chance making our daily quota.There were structurally technical poblems making our work more difficult. Firstly the spool jumped out of the saddle of the spinning wheel. The yarn would not wound around the spool. Secondly the spinning wheel ‘walks away’ from you and thirdly sometimes the flax is not of th ebest quality (bongkoh). Instead of pulling a piece of fiber you pulled the whole bundle from under your arm pit and you fouled up your whole processing” (…)

The B29 flying over

Awareness of time merely was lacking. Harley and the other boys did not know which day, which month or year they were living in. The Japanese controlled means of communications and did not inform them about what happened outside the premisses. Contact with the outside world was reduced.Every third Sunday of the month the children were allowed to visit our parents, but had to be back at 5.00 pm at the same day. 4)

The Japanese only gave orders no other information.

Harley Driessen:

Then one day:

“…a B 29 Glenn Martin bomber flew over us. Most important: it was not a Japanese plane but a Dutch one. At the double tail there were the red, white and blue colors , the national colors of the Netherlands. The plane flew over our area dropping leaflets. They all fell outside our reach so I never have known what was the content of those leaflets. The rumour then was spread around that an impending invasion was to expect or something else is going to happen and that war was almost over.” (…)

“Not long after Flying Fortresses flew over Semarang harbor and started bombing. First they shot those light bullits illuminating the whole area followed by falling bombs. From where we were we only could hear them exploding. Later, we saw the sky turns red from the burnings.” noot)

Hunger and survival

The lasting war situation meant an increasing Japanese pressure on peoples productivity and availabilty of commodities. The Japanese war economy was in an endless need of raw materials, foodstuff and labor force. This all at expense of the internees and Indonesians.

The boys in the orphanage were not excepted from the worsening daily life conditions and had to find out how to survive:

“As growing kid we were always hungry but no way we knew how to stop that need. Maybe calling it a real hunger was a misnomer. We were just craving for something to eat. At that time we thought nothing wrong about stealing food. In fact you would be a hero for not getting caught while stealing. Being caught would make you the laughing stock of the group. Then you would feel ashamed of yourself or dumb as you were caught. So we felt stealing food was not a serious offense. Later, as we grew older we became aware our way of thinking was morally wrong.” (…)

The friars and pupils of the Rooms-Katholieke Jongensweeshuis after the end of World War II.

Photo: private collection Harley Driessen

Japanese Capitulation and Indonesian War of Independence

August 15, 1945 did not mean the return of the Dutch in the archipelago. In the meantime Indonesian nationalists took position in Semarang trying to put the area under its control. Dutch and Indo people in and outside internment camps were not safe for Indonesian extremists. In Semarang and places in the neighbourhood Ambarawa and Salatiga the Japanese had interned many Europeans who now had to rely on the former ennemy for their protection against the radical and violent young revolutionaries (pemudas). Downtown Semarang was occupied by the Indonesians but as by a miracle the Sint Jozefschool kept unharmed. According to the orders of the Allied supreme command British troops had to put the archipelago under their rule and control. As the extremists occupied parts of Semarang and not willing to hand over control, the British attacked the town. Indonesian resistance was strong and the town had to be conquered street by street:

“There were street fights. We could see the Japanese went from house to house. We witnessed these fights and we heard the bullits wistling nearby. We were not allowed to stay outside anymore”.

Soon the boys in the orphanage were ordered to prepare for leaving the premisses.

Harley Driessen tells:

“The animals were the first things to go. All hens, roosters and chickens were slaughtered and eaten. Oh…. yes, we also had rabbit. Each kid received a knapsack to put in their belongings. D-day was a Sunday.We waited and waited but eventually nobody picked us up. The whole evacuation deal fell through.

Later on we heard the internees coming from the vast Ambarawa camp (40 km south of Semarang) had been given priority. The surroundings were under Indonesian control and the nationalists were about to overrun the camps. The Allied forces were not able to defend the place and decided to leave Amabarawa. The internees were hauled into a great number of trucks. These were packed and covered with molton blankets to protect the passengers from shrapnell in case the convoy would be attacked. As soon as the trucks left the camp was attacked. The trucks went straight tot the Semarang harbor and the evacuees were sent to Siam (Thailand). This is the story I heard.”

Back to the Rooms-Katholieke Weeshuis Tjandi

When Dutch authority was re-established in Semarang the Sint Jozefschool would be a school again. So Harley Driessen moved to the Rooms-Katholieke Weeshuis but not after having put back all the furniture in its original state. During the war the church building had been used as a storage place and in order to function as a church it needed to be emptied. It took a while before the job was finished.

Notions about the education

Fortunately the orphanage not only assigned the pupils with labor or similar activities. When the building had been made ready again school started. The war meant an interruption of the regular rythm of school. Harley Driessen tells he was already ten years old when he was a second grader in elementary school:

“instead of an annual gradation we graduated every six months. Within three years I was in seventh grade and when I was 13 years old I graduated from elementary school in 1948. We continued the education outside the orphanage. My next school was run by brothers of a different order: the Immaculate Conception. I stayed there for four years and the curriculum was the equivalent of high school. After I visited the Sekolah Tehnik Menega or Technical School during a new period of four years. After my graduation brother Maxentius, the director of the Rooms-Katholieke Weeshuis told me I then had to leave the institute as its task had been fullfilled. September 29, 1956 I left the orphanage and went to my eldest brother who lived in Surabaya.”

Opting Indonesian of Netherlands Nationality?

The Indonesian government offered Dutch nationals (especially meaning the Indos) the option to become an Indonesian national, warga negara, or to keep Dutch nationality. Harley Driessen:

“I asked brother Cosmas to arrange for me to provide me with a Dutch passport. I did not tell brother Cosmas that I actually had the Indonesian nationality already.”

Then the director went to the Hoge Commissariaat (the commissioner charged with all matters concerning Dutch nationals and Indos in Indonesia). Later, in the Netherlamds in 1959, Harley Driessen had to apply for the Dutch nationality which he considers with hindsight the most important decision of his life.

Social Assistence from the Dutch Government pending Repatriation to Holland

Emigration to the Netherlands meant also resolving practical problems as how to finance the passage, finding work and a the housing. Fortunately the Dutch government provided to a limited extent financial means. Many Indos could have an advance payment in order to buy a boat ticket. Later they should amortize the loan.

Also Harley Driessen was in the running to receive government support but he had to wait about one year before he actually would leave.

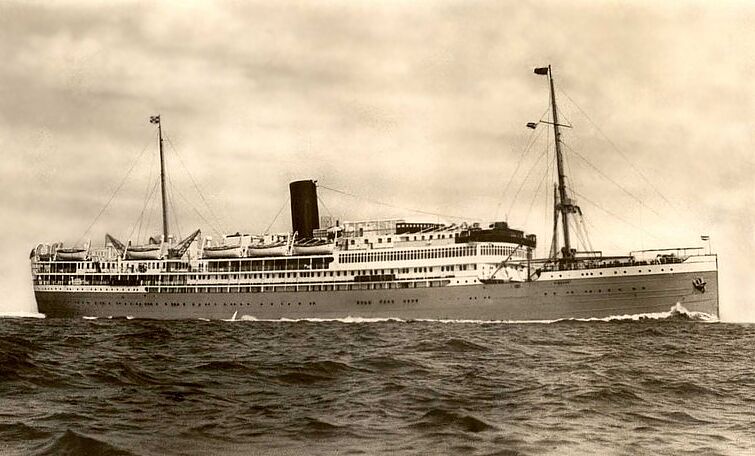

“After a year or so the Dutch Hoge Commissariaat notified me a place was available on the ship ‘Sibajak’. I made the needful arrangements and left Indonesia alone without mother, brothers or sisters. They went to the Netherlands later. The passage was based on an advance payment but I had to pay it back later in guilders, then a ‘hard’ currency and therefore it was an expensive loan that I would pay back during many years. The Indonesian roepiah was a weak currency which had lost a lot of value because of the deteriorating political and economic circumstances in the young republic. Anyhow, before I left the country I wanted to get rid of my roepiahs and bought guilders but had to notice I had no money at all. The money must have fallen out of my pocket when cycling. When I boarded the ship I had no money at all. After we passed the harbor of Port Said in Egypt I received my first three guilders from a Dutch official. I supposed to get it every week as long as I was not yet working in the Netherlands…”

Harley Driessen arrived in the Netherlands after a passage of 28 days.

1956: the Sibajak bringing Indo and Dutch repatriates to the Netherlands. Among them Harley Driessen

Be continued

Notes

1) According to Harley Driessen the term ‘orphanage’ is a misnomer. Most of the children still had their parents, including me, but were in the orphanage for many different reasons.

2) Harley Driessen: It is not only the root that you can eat, but also the leaf that grows on the stem (the young leafs of course). The whole thing is called the cassava plant. The stem itself, you cut it in pieces and put it in the ground again (the correct way. Upside down the root is poisoners). Six month later you harvest the next cassava. One plant produces several roots (large or small ones). The roots all become what we called the cassava. You could eat almost everything what the cassava root produces.

3) Harley Driessen: the name is Karel Bauwer or Bauer. I am not sure which one is the correct spelling.

4) Probably the bombardment was July 22, 1945 or the next day. According to other sources and witnesses the planes were B-17 or ‘Flying Fortresses instead of the B 29 Super Fortress. Harley talks about B-29 Glenn Martin planes: the type Glenn Martin bomber of the KNIL (Royal Netherlands Indies Army) was the B-10.

Pingback: Nieuw gepubliceerd: Harley Driessen, Indo van Semarang naar San Lorenzo (eerste deel) |

REACTIE OP “AMERINDOS | AMERINDOS 8. HARLEY DRIESSEN FROM SEMARANG TO SAN LORENZO (1)”

Beste meneer Driessen,

Ik ben al enige tijd op zoek naar informatie over mijn vader, geboren in 1911. Hij is opgegroeid in het jongensweeshuis in Semarang, zijn 2 zussen in het meisjesweeshuis. Na een zoekactie op internet heb ik uw verhaal gevonden, al lezende zag ik de foto waarop tussen de broeders een man gefotografeerd is met een kort wit jasje. Kent u de namen van deze mensen, in het bijzonder van de man in het korte jasje? Mijn vader had een heel goed contact met de broeders en ik kan me goed voorstellen dat hij na de oorlog het weeshuis heeft bezocht. Ik vraag me dus af of mijn vader op deze foto staat.

Ik hoor graag van u,

met vriendelijke groet,

Joyce Pontororing

Dankuwel voor het delen van uw herinneringen!

Mijn vader, Evert van Westering (geboortejaar 1928), heeft ook in die tijd in het weeshuis in Tjandi gezeten. Ook zijn broers, waaronder zijn jongere broertje Ben, hebben er gewoond. Helaas leeft mijn vader niet meer om zelf over die tijd te vertellen, maar dankzij uw verhaal heb ik nu toch wat meer een beeld van gekregen. Heel fijn!

Ik kwam in juni 1949 in het weeshuis van Karangpanas. Daarvoor zat ik bij de zusters van De Goddelijke Voorzienigheid in Kebon Dalem tussen Chinese weeskinderen. De zusters waren erg streng, maar ik vond ze ook wel erg lief. De broeders op Karangpanas vond ik alleen maar streng, soms zelfs wreed (vooral Br. Wilfried). Na jouw verhaal te hebben gelezen ben ik pas gaan begrijpen waarom ze zo waren en heb meer respect voor hen gekregen. Ik ben trouwens later ook broeder geworden (van 1956 tot 1964). Dank voor jouw verhaal